Shohei Ohtani Is an Icon Among Us

Part 1: The Gloves

Pure joy. The peal of wedding bells. The spring sonata of a songbird. And this. Elementary schoolchildren at play.

Shohei Ohtani is listening to and watching them smile and shriek in the delight that only the innocence and wonder of youth allow. The world will teach them anxiety, duplicity and cynicism. Not now. Not here. This is the music of joy.

“It had a special feeling to it!” gushes one boy in Japanese. “It had a signature on it! I was happy to touch it!”

Ohtani is watching a three-minute video on a phone. He is seated in the bedroom of a suite on the 47th floor of a midtown New York City hotel, the spires of St. Patrick’s Cathedral below and the Hudson River due west. He is wearing a moto-style black leather jacket over a white silk T-shirt and a pair of dark indigo jeans. He is listed at 6' 4" and 210 pounds and projects even more size up close. But like an Italian sports car, even at rest his angularity and aura connotate agility and speed. The power is all under the hood.

[ Buy now! Shohei Ohtani on Sports Illustrated’s April 2024 cover ]

With him are his two most trusted friends. To his left sits Ippei Mizuhara, his training associate, ride-or-die buddy and translator. Behind him, curled comfortably on the bed, is his dog, Dekopin, also known as Decoy, a Kooikerhondje who, befitting his status as the pet of the most prolific two-way baseball player who has ever lived, is bilingual. Of course he is.

“I have not seen this before,” Ohtani says as the clip plays. He is smiling as he watches. In December, Ohtani donated 60,000 baseball gloves to the nearly 20,000 elementary schools in Japan. Two right-handed gloves and one left-handed glove for every school. Though most of the gloves arrived while schools were on Christmas break, word of Ohtani’s donation caused the school playgrounds to fill. Boxes are ripped open, and gloves held aloft like the Golden Fleece. Some city officials put the gloves in glass cases like museum pieces, drawing swift rebukes from the populace that understood Ohtani’s intention.

“I heard that new gloves were coming, so I got up early,” another boy says in Japanese. A school staff member adds, “I was really looking forward to seeing the gloves. It’s not a workday today, but I just had to come.”

The boys and girls play catch. Playing catch is the most beautiful game within the most beautiful game. A way to connect. A shared experience. An eternal exercise in what it means to give and take. “I think it will be a very good memory,” says one school administrator, “so I would like to say thank you very much.”

One group of boys and girls gather to shout a message to Ohtani: “Yay! It’s the best Christmas present! Yay! Merry Christmas!”

The video ends. Ohtani lifts his head. He is smiling, just like one of those children. “Honestly, this isn’t the end,” he says. “I want to keep doing this, so I’m glad it’s just the beginning.”

The donation was Ohtani’s idea. He had recently renewed his endorsement deal with New Balance, part of a suite of sponsorships that will earn him $50 million a year off the field. Then, on Dec. 11, as a free agent he signed the richest and most unique contract in sports history. The Dodgers will pay him $700 million—at his request to ease the financial burden on the club, he’ll receive it at a rate of just $2 million annually for the next 10 years and $68 million for 10 years after that, with no deferred interest.

The gloves are his way of sharing his success. They also are one of the totems that help explain why Ohtani is a modern unicorn, one of the most popular athletes on the planet even without trying to be. This will be one of his rare allowances of self-reflection: Ohtani on Ohtani. The donated gloves are a good place to start.

“The idea came from signing with New Balance and with the Dodgers,” Ohtani says. “Basically, it’s money coming from the fans. So, I wanted to give back in return. It’s not just about the current situation. It’s about the future. About baseball. Well, I think it’s normal to turn it around to some extent.

“So, they will be playing baseball in some type of way. The basic of baseball is playing catch with the glove to start with. So, I came up with the idea. When I thought about it, I thought it might not make immediate impact, but I think by continuing to do stuff like this down the road it can help out in a big way.”

Ohtani thinks about his first glove. He was 5 or 6 years old. It was a hand-me-down from his older brother, Ryuta. The glove was a well-worn, dark brown hunk of leather. Two years later, in second grade, Shohei joined his first team in an organized league, one that played with a rubber ball. To mark the occasion, his father, Toru, an outfielder on a corporate-sponsored amateur team, bought Shohei the first glove of his own: a two-tone Spalding beauty in red and black. Only after the purchase did Shohei discover the league did not allow multicolored gloves. He grabbed a black Sharpie and made his first baseball glove league compliant.

Toru served as one of Ohtani’s coaches from those elementary school days through junior high, including as the manager of his teams from ages 9 through 12. “I was in a tougher spot because I was the coach’s son,” Ohtani says. “I didn’t want to be getting playing time just because of that. I had to actually prove that I was good enough. So, that was like a challenge during those times.”

Part 2: The Notebook

One day when Ohtani was 9 or 10, Toru bought a small, college-ruled notebook. After games or practices, Toru would write messages to his son about his performance. Maybe it was to compliment him on the command of his pitches that day. Maybe it was to point out that he had chased a few pitches out of the strike zone. Maybe it was to remind him to value every detail of practice, right down to a simple warmup throw. He would then hand the notebook to his son.

Maybe a day or two later, Shohei would hand the notebook back to his father after writing down his own observations and assessments. Shohei was keen on writing down his goals—the championships he wanted to win, where he wanted to be as a player by next week, by high school, by age 30, etc.

A few days later, it was again Toru’s turn to write. And then back to Shohei. And so on and so on ... a game of literary catch that went on for about four years. Father and son filled three notebooks. Toru often repeated three messages to Shohei: Always be loud and clear with communication on the field, always hustle and always be very purposeful about playing catch, honing accuracy and technique rather than treating it as a boilerplate warmup routine. The overall theme was one of unwavering intentionality, be it in a game or practice. Writing down the words to one another gave the lessons an enhanced value to young Shohei. They acquired a permanence in his mind.

Today Ohtani is one of the most famous, beloved and richest athletes in the world. When he announced his decision to sign with the Dodgers Dec. 9 on Instagram, he had 6.2 million followers; he’s now up to 7.1 million. Fans in Tokyo and in the northeastern prefecture of Iwate, where Ohani grew up, lined up to buy special editions of newspapers. (The man sells newspapers!) Others swarmed to his high school and jostled one another to get pictures of a monument to him that shows his ... handprint. Others rushed to Japan Post Co. to drop 7,260 yen (about $48) to snap up the Shohei Ohtani Premium Stamp Set, which features five stamps and 44 postcards—one for each of his American League–leading home runs last year. The apparel company Fanatics said more Ohtani Dodgers jerseys were sold in the first 48 hours of release than any jersey in their history, eclipsing sales of soccer stars Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi. Seventy million people watched Ohtani’s introductory news conference at Dodger Stadium on Dec. 14. Seventy million—a larger audience than any World Series game in history.

In 2022, citizens of Japan picked him as the country’s favorite person or topic of the year, outpolling a wildly popular Japanese manga and anime series and the World Cup. A poll last summer found that 22.3% of people aged 12 to 21 chose Ohtani as their favorite athlete. No one else drew more than 3.1%. “We’re already seeing the response and level of interest we’re getting from fans and sponsors is far greater than we even expected,” says Dodgers executive vice president and chief marketing officer Lon Rosen.

Rosen traveled to Japan in January to meet with companies eager to become a Dodgers sponsor. He was blown away by how many CEOs had veritable shrines to Ohtani in their boardrooms and offices. And yet ... the wonder of Ohtani is not found in the enormous wake of interest and money he generates. It is found in those small children showing up at school when there is no school just to slip their hand into a baseball glove donated by Ohtani.

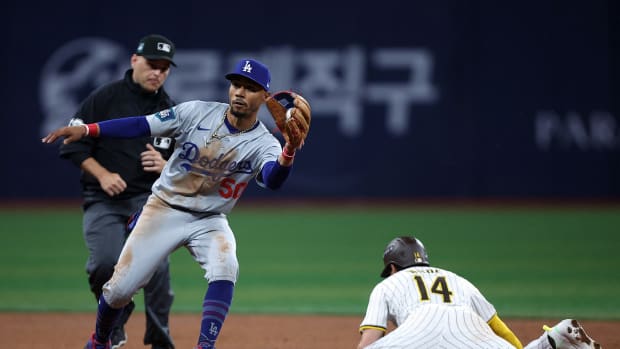

The last year has brought him simultaneously to new heights of popularity and humility. He clinched the World Baseball Classic championship for Japan by striking out then-Angels teammate Mike Trout (above)—after volunteering to warm up in the bullpen between his at-bats as a DH, while most top American-born pitchers opted out of the tournament. He won the AL home run title and the Most Valuable Player Award, unanimously. He offered to defer 97% of his record contract without interest, gifted a Porsche to the wife of Dodgers pitcher Joe Kelly in appreciation of his giving Ohtani uniform number 17, and in conjunction with the Dodgers donated more than $1 million to relief efforts in western Japan after it was struck by a New Year’s Day earthquake. This is a superstar who is so fastidious and proper he routinely stoops to pick up gum wrappers to keep the dugout floor clean.

“I’ve been around some of the biggest athletes in my 40 years or so in sports,” Rosen says. “Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, Mike Tyson, Pele. I have never seen anyone like Shohei, especially his popularity in Japan. He is revered not just because he is a sports figure. Like M.J. and Magic, he has that special something that people see he is authentic.

“He’s got that special quality to be so enormously talented and still everyone feels like, ‘He’s just like me.’ There are no airs of cockiness or superiority. They see him for what he is: a very thoughtful, humble person.”

Part 3: The Dog

Seven years younger than his older brother, Ohtani as a child wanted to be a big brother himself. So one day when he was in first grade he asked his parents, Toru and Kayoko, for a dog. They got him a Golden Retriever. They named him Ace. His love of dogs would play a role in Ohtani becoming the two-way player he is today.

As a high school senior in 2012, Ohtani told teams in Nippon Pro Baseball not to draft him. He was going to sign with a major league organization. The Dodgers, who had scouted him since he was a freshman, were considered the front-runners, with the Red Sox and Rangers also in pursuit. Dodgers assistant GM Logan White at the time compared him to Clayton Kershaw, saying Ohtani could be pitching in the big leagues within two years. He called him “an interesting prospect as a hitter.”

On Oct. 25, 2012, the Nippon Ham Fighters drafted Ohtani. He said there was zero chance he would sign. A week later, staff members from the Fighters visited the Ohtani home. Upon arriving they first gave attention and love to Ace. Kayoko noticed. People who love dogs, she thought, are good people.

Fighters manager Hideki Kuriyama met Ohtani twice to convince him to establish his bona fides as a two-way player in Japan before joining the majors, where teams were more likely to commit him to specialization as a pitcher or hitter. At the first meeting, Kuriyama wore purple underpants to honor Ohtani’s high school colors. At the second one, the meeting that clinched the signing, he wore beige underpants to honor Ace.

Ohtani signed and lived in the Fighters’ team dorm, a requisite for first-year players that he opted for even as he became a star. Ace remained at the family home. One day when Ohtani was on the road with the Fighters, Ace died. Ohtani had been without a dog ever since.

Last season Ohtani, who had Tommy John surgery in 2018, reinjured his throwing elbow on Aug. 23. He decided to finish the season with the Angels as a DH only, but on Sept. 3 he strained an oblique muscle, an injury that would sideline him for the rest of the season. There was no need to postpone the elbow procedure. On Sept. 20, Dr. Neal ElAttrache, who performed the original Tommy John surgery, also handled this procedure, which differed from the first.

In a statement ElAttrache said he repaired “the issue at hand” while reinforcing “the healthy ligament in place while adding viable tissue for the longevity of the elbow.” Two sources familiar with the procedure indicated ElAttrache built an internal sleeve or “brace” around the repaired area for long-term stability. Ohtani expects to return to pitching in 2025.

Around the time of the surgery, Ohtani met a dog breeder who loves baseball. Ohtani knew the procedure would keep him at home and inactive for months as he rehabbed. “I felt like it was the perfect timing [to get a dog],” Ohtani says. “I had to be home and not do anything, so I felt like it was perfect timing.”

The Kooikerhondje breed dates to the 1500s in the Netherlands. Taking their cue from similar behavior they saw from foxes, hunters bred the dogs to cavort on wetlands to attract waterfowl, whereupon they would lure the birds into a trapping or cage system. The English word “decoy” derives from the Dutch word for “the cage,” de kooi. In modern times, the Kooiker has gained a reputation as a faithful, easygoing companion dog, as Ohtani attests.

“There’s a dog park right in front of my house,” Ohtani says. “I would take him there twice a day. Once during the day and once at night. Then in the meantime, I’d come back and I would do my rehab stuff, like in an armchair. Then we would match up our time to eat together.

“We were kind of just chill. That was like our daily routine, until I signed with the Dodgers. I started going to Dodger Stadium after that.”

The companionship eased the monotony of rehab. “Going for a walk after the surgery was a change of mood,” Ohtani says. “It was refreshing and a lot of fun. I feel like [the rehab] is shorter than the last time.

“I can’t live freely outside, so it’s nice to be able to stay inside the house. I mean, I’ve been living by myself for a long time. I didn’t really have anybody. So having someone that’s always with me and shows me love all the time, it’s been really great. Like now I’m sleeping with him.”

The dog made his national television debut on Nov. 16, when Ohtani made an appearance on MLB Network upon winning his second MVP. Producers were told not to ask the dog’s name. Rumors circulated that the dog’s name might be a clue to the team that would sign him as a free agent.

When Ohtani made a recruiting visit to Dodger Stadium on Dec. 1, the Dodgers pulled out all the stops. They gave him a tour of the facilities and bragged about their minor league system. Then president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman pulled out his phone.

A week or so earlier, Friedman was sitting with Rosen and general manager Brandon Gomes. They remembered that in 2017, when Ohtani was a free agent after leaving the Fighters, the team asked Lakers great Kobe Bryant to film a recruiting video. The Dodgers planned to show it to Ohtani at their second meeting. But they never got that second meeting. The National League had no designated hitter at the time, a position that better facilitated Ohtani’s two-way plans. He signed quickly with the Angels.

“I’ve still got it on my phone!” Friedman told Rosen and Gomes. “How great would it be if we showed it to him this go-round?”

Bryant died in 2020 in a helicopter crash. Friedman showed Ohtani the Bryant video that had been in his phone for six years. “You could tell he was touched,” Friedman says. “It was perfect, with Kobe being the ultimate competitor. Because in our minds, Shohei exhibited the same behavior in the WBC with his intense level of compete, especially the final.”

The Dodgers had one more surprise. They waited until the end of their three-hour meeting, then handed Ohtani a gift box. He opened it and immediately burst out laughing and smiling. It was filled with Dodger-themed dog chew toys. It might have been the biggest hit of the day.

“It was our secret weapon,” Friedman says.

Two weeks later, at the introductory press conference in front of more than 300 photographers and journalists, it took 10 questions for the big one to come up: “What is the name of your dog?”

Ohtani revealed the dog’s name is Dekopin, a Japanese name for flicking someone’s forehead with a finger in a schoolyard prank. He also allowed an English version of the name that is true to the breed’s heritage: Decoy.

Ohtani hadn’t planned on bringing Dekopin with him in January for the two-day trip to New York, where he accepted the MVP at an annual awards dinner. Mizuhara’s wife takes care of Dekopin when Ohtani is away. But as he was leaving Southern California, Ohtani could not bear to leave the dog behind. He changed his mind. In New York, while wearing a festive red-plaid sweater, the dog demonstrated how he responds to commands in both English and Japanese.

“He’s very well-behaved,” Ohtani says. “He had like, um, potty issues in the beginning. Of course, it’s natural. But the first time he succeeded was the day I signed with the Dodgers. It was a big day!”

Part 4: The Deferral

Late in the day on Dec. 7, Friedman’s phone rang. It was Nez Balelo, Ohtani’s agent. It was the first time Balelo presented the idea of Ohtani deferring nearly all of a $700 million contract without interest. One word, Friedman says, immediately popped into his head. Deal!

That kind of deferral was so stunning, so unheard of, that the idea of presenting such a proposal to a player seemed preposterous to Friedman. He would have never asked for such a thing, but now here it was in his hands.

“After I had time to process it, I understood it was so consistent with everything Nez and Shohei had said along the way,” Friedman says. “Often times, you hear words in negotiations and the actions don’t match it. In this case the actions exactly matched their words.”

Friedman and Balelo, who still had other teams interested, agreed to talk again the next morning in more detail. After he hung up, Friedman dialed Dodgers president and CEO Stan Kasten.

“Holy f---,” Friedman said.

“Is that a ‘Holy f---’ good or a ‘Holy f---’ bad?” Kasten asked.

“Good. Very good.”

The deferral idea had percolated in Ohtani’s mind for weeks. Ohtani had never come close to signing an extension with the Angels before the 2023 season. Owner Arte Moreno was worried about how high the money would get. He had signed Trout to a 12-year, $426.5 million extension that began in 2019, the richest contract in baseball, and had given a seven-year, $245 million free agent contract to Anthony Rendon, the richest average annual value ever for a third baseman when it began in 2020. Combined, they missed 52% of L.A.’s games from 2020 to ’22. Moreno figured a contract for Ohtani would “start with a 4,” according to a source familiar with the team’s planning. The Angels and Balelo agreed to play the season out and address the future then.

The Angels opted to not trade Ohtani last summer, which led to a free agent bidding war after the 2023 season.

Winslow Townson/Getty Images

At the trade deadline last July, the Angels were 56–51 and three games out of a wild-card spot with 55 games to play. The team had not reached the postseason in nine years. Moreno wasn’t about to forfeit this chance. He kept Ohtani off the trade market, while knowing he was unlikely to retain Ohtani in a free agent bidding war.

The Angels immediately began to sink. They lost seven in a row, igniting a 17–38 freefall. Ohtani injured his elbow and then his oblique. After more breakdowns by Trout and Rendon (they missed 61% of possible games last season), Moreno told Balelo early in free agency he was out on Ohtani, the source said.

Meanwhile, the Dodgers made an important early connection with Balelo on Ohtani’s value. The agent had a player unlike anyone in free agent history—not just because he was an elite two-way player but also because as an international icon Ohtani generated huge residual value to a franchise. Two Angels sources estimated Ohtani generated between $20 million and $25 million in annual revenue for the franchise. But the Angels also were a team that never finished fewer than 10 games within first place with Ohtani. He had never seen a true pennant race or the postseason as a major leaguer.

Balelo knew Ohtani’s value would soar after the WBC championship, after another MVP season and with the right competitive team—especially as franchises were just establishing the value of sponsorship uniform patches, which seven teams unveiled in 2023. Balelo armed himself with data to support an approximation of that value. Some teams questioned its accuracy. The Dodgers got it. Balelo never had to sway them on what Ohtani could generate.

The Yankees sold their uniform patch this year (along with other advertising agreements that come with it, such as stadium signage) for a reported annual value of $25 million. The Dodgers, according to two sources familiar with such talks, were seeking a more lucrative deal because of Ohtani. The sleeve of his jersey became one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in baseball, especially given the unprecedented level of social media and online impressions. Guggenheim Baseball Management, the consortium that owns the Dodgers, grabbed the space itself. Terms were not announced.

Once Ohtani told Balelo about the deferral idea, the agent went to work to devise the best structure for his client. He dug into the Basic Agreement and found the only stipulation about deferring salary is that a player must earn at least the minimum salary, which is $740,000 this year. Balelo also found that the largest chunk of money previously deferred was 50% of the $210 million contract Max Scherzer signed with the Nationals in 2015.

Balelo came up with a structure that impressed the Dodgers and, since Ohtani has so much current endorsement money, also positioned his client well for savings when his deferrals kick in from 2034 to ’43. For instance, if Ohtani is not living in California then, he could avoid the 13.3% state tax and 1.1% payroll tax for State Disability Insurance. Under that scenario, Ohtani would save $98 million in state tax, according to the California Center for Jobs and the Economy.

In January the state controller, Maria M. Cohen, responded by asking Congress to “take immediate and decisive action” against unlimited deferrals by establishing “reasonable caps.” Two years ago, Ohtani’s uniqueness caused MLB to rewrite its rules; the Ohtani Rule was created to allow a pitcher removed from the mound to remain in the game as the DH. Now California wanted an Ohtani Rule for its tax code.

Balelo and Friedman resumed their conversation on the morning of Dec. 8. “When I got off the call,” says Friedman, “I felt pretty confident. And about 60 minutes later, I started hearing about reports that he had agreed to terms with Toronto, and he was in the air on a flight there. I wasn’t sure what to think. The level of detail in some of the reports made me think it was genuine.”

Helping lead Team Japan to a WBC championship victory over Team USA was a pivotal moment in Ohtani's career.

Rob Tringali/WBCI/MLB Photos/Getty Images

A plane was identified leaving John Wayne Airport in Orange County for Toronto. It quickly became the most tracked plane in the world.

Friedman dialed Balelo. No answer.

At that moment Dodgers manager Dave Roberts was playing golf at Rancho Santa Fe Golf Club with Brian Bumgarner, the actor from The Office. Roberts’s phone was blowing up with texts from his son and friends telling him it looked like Ohtani was signing with the Blue Jays. “Probably the worst round I ever played,” Roberts says. “I couldn’t get locked in. I wasn’t feeling good about it.”

Friedman stewed. It seemed longer, but it was only 10 minutes later that the agent called him back.

“Sorry, I was on another call,” Balelo said.

“What about these reports that he’s on his way to Toronto?” Friedman asked.

“Those reports aren’t true. He’s home. He’s sleeping now. I’m going to see him later when he’s working out.”

The false reports continued. Meanwhile, Balelo kept in touch with other teams. Friedman says Balelo told him he was taking the deferral plan to other clubs. Giants president of baseball operations Farhan Zaidi later said his team made an offer “very comparable if not identical” to the final deal, both in “structure and compensation.”

Balelo circled back to Moreno and the Angels one last time. He caught Moreno on the phone while the owner was sitting down for lunch in Phoenix. Moreno still wasn’t interested. The proposal of huge deferrals changed nothing for him. He remained out on Ohtani.

Ohtani made his decision that night. He told Balelo he wanted to play for the Dodgers. They drafted an announcement to be posted on Instagram the next day. About five minutes before the post, Balelo called Friedman with the news.

Something the Dodgers had told Ohtani during his recruiting visit had made a powerful impression on him. Friedman and principal owner Mark Walter emphasized the franchise was not satisfied with having won one title in their 12-year run of playoff appearances. They promised him they would continue to field competitive teams throughout the life of the contract.

“Of course, I’ve always imagined myself in the postseason,” Ohtani says. “I couldn’t play last year [if the Angels made it] but I’ve always had that image.

“Before the WBC, I hadn’t really been playing in those win-or-go-home games. It’s been a while since I played in that. So, playing those types of games in the WBC was really, really fun and refreshing and made me more hungry to play those types of games, which is equivalent to the playoffs and in the World Series.”

Part 5: Genius

Albert Einstein learned to play the violin as a child. What often had seemed like drudgery exploded into passion at age 13 once he heard the sonatas of Mozart. “The music of Mozart,” Einstein later said, “is of such purity and beauty that one feels he merely found it—that it has always existed as part of the inner beauty of the universe waiting to be discovered.”

Change “the music of Mozart” to “the play of Ohtani” and Einstein’s observation on genius rings just as true. Ohtani has not created something new. He has not introduced a new pitch or a new batting style. He has found the inner beauty of the game that had been waiting to be discovered in the majors since 1919, when Babe Ruth ended his two seasons of two-way duty.

Ohtani hits. He pitches. Science and music. Purity. Harmony. Genius.

When he was 12 years old, Ohtani wrote in his notebook that he wanted to play in Japan’s equivalent of the Little League World Series. For good measure, he also wrote his goal on the back of his cap. He achieved it. He is asked whether his 12-year-old self imagined that at 29 he would be the world’s greatest two-way player.

To watch Ohtani train is to understand whence his genius derives: from those childhood notebooks. Here he is truly his father’s son. The lessons of diligence, of valuing the smallest components of work—each rep, each swing, each throw—all resound here.

Ohtani is a physical marvel. Last season he hit the ball harder than anybody in the AL (94.4 mph average exit velocity, minimum 2,000 pitches) and hit the longest home run in all of baseball (493 feet). In 701 career games, Ohtani has hit 171 homers and stolen 86 bases. Nobody else in the history of the game began a career at those thresholds—and he did so while also striking out the eighth-most batters in any pitcher’s first 86 games. He has freakish shoulder flexibility and so much power in his legs that his vertical jump and power off a force plate measuring device were as high as the Dodgers have recorded since they adopted the technology.

Combine those physical tools with the intentionality he developed with his father, and you get genius. Recovering from his elbow surgery, Ohtani began hitting again in January. Ohtani treated each practice swing like a game swing. Each time he carefully settled his feet in the proper spots, windmilled the bat gently in front of him, placed the bat on his back shoulder while loosening his grip as if playing the flute, then lifted the bat high and straight in that familiar posture. Only then was he ready to whack a baseball flipped by a coach.

“That really stood out,” Friedman says. “I’ve seen guys go through their return-to-play progression and they go in and mindlessly take swings any given day. His patience and purposeful nature extend to that work and how he would take 15 to 20 seconds between swings and go through his pre-pitch routine every swing.”

Swing by swing, weight by weight, sprint by sprint, Ohtani challenges himself as if still writing to Toru in the notebook. “Yes, if I had to pick I would say I am the goal-setter type,” Ohtani says. “Especially when it comes to lifting. You have to have a plan. You just can’t be doing anything you want. It’s not going to work out. Set a good goal and the plan to get there.”

As a child, Ohtani enjoyed swimming and badminton, which his mother played. The son of one of his mother’s teammates played baseball and invited Shohei, then in second grade, to join the team. He was drawn to the game anyway because his brother and father both played. A natural righthander, Shohei asked Toru if he should bat left-handed or right-handed. “And he told me, ‘Hey, stand up and let me see your stance,’ ” Ohtani says. “And my stance was left-handed, so ... ”

So began the love affair between Ohtani and baseball. It has been said that baseball is a game of failure, with the best hitters making seven outs every 10 at-bats. But the other side of that coin is that it is a game that rewards diligence. Its greatest rewards come from slow-growth investments, not instant gratification. Having to methodically earn your way is what gripped Ohtani.

Asked what gives him the most joy about baseball, Ohtani does not choose home runs or strikeouts. He chooses the process it requires. “It’s also about setting goals,” he says. “My first goal was to play in the national tournament. And I was actually able to play there. It was a joy that led from the result of my practice. I don’t think it had to be baseball, but for me, it just happened to be baseball. I love setting goals and achieving them.”

This season, media buzzwords such as “pressure” and “expectations” will hang around Ohtani and the Dodgers like a swarm of gnats on a steamy summer night. Those are stock narratives. Ohtani is the antithesis of a stock player. “What I’ve noticed most about him,” Roberts says, “is his ability to manage the noise around him and stay focused in the moment. That’s the intentionality of his work. Everything he does is thought through. Every day is calculated. There is also a humility and softness to him.”

Softness? It is the rare time the word is offered in high praise of an athlete.

“That comes from his upbringing and his culture,” says Roberts, whose mother, Eiko, was born in Okinawa, Japan. “There is a certain respect of how you do things and how you treat people, as well as an inner confidence.”

There is another word that better captures Ohtani. In Japan, to be an expert craftsman is to be revered as a shokunin. The term loosely translates in English to “artisan,” such as a skilled potter, poet or painter. An artisan Ohtani certainly is. But shokunin carries a much deeper meaning beyond a mastery of individual skills.

For instance, soon after Ohtani deferred $680 million, the Dodgers poured a combined $461 million into free agent pitchers Yoshinobu Yamamoto and Tyler Glasnow. Ohtani not only helped make it possible, he also helped recruit both. To the shokunin, the greater good matters.

A shokunin like Ohtani is more than an artisan. A shokunin venerates natural material and tools, respects and honors the time required by proper diligence and always produces work in the context of social responsibility. The shokunin truly succeeds not on individual merits, but for the betterment of the community.